In this case, the Court:

- Determined that a climate emergency that seriously threatens humanity, and especially the most vulnerable people, exists. It can only be adequately addressed through urgent and effective mitigation and adaptation with a human rights perspective;

- Decided that, in the context of the climate emergency, States have general obligations, including a) to respect rights, (b) to guarantee rights, (c) to ensure the progressive development of economic, social, cultural and environmental rights; (d) to adopt domestic law provisions, and (e) to cooperate in good faith;

- Found that the recognition of Nature and its components as having rights reinforces the protection of the integrity and functionality of ecosystems;

- Determined that the prohibition of conduct that may cause irreversible harm to the vital balance of common ecosystem that makes the life on Earth possible constitutes a peremptory norm of international law;

- Recognized the right to a healthy climate, as a component of the right to a healthy environment. In its collective dimension, it protects present and future humanity, as well as Nature;

- Found that States have specific obligations derived from substantive rights, including obligations:

- to protect the global climate system and prevent human rights violations resulting from its disruption;

- to mitigate GHG emissions, by adopting a mitigation target and strategy, as well as regulating the conduct of corporations; and

- to define and update, as ambitiously as possible, their national adaptation goal and plan;

- Determined that States have specific obligations derived from procedural rights, including access to information, political participation, access to justice, the right to science and the recognition of local, traditional and indigenous knowledge. They also have a special duty to protect environmental defenders;

- Decided that States must adopt measures to address how the climate emergency exacerbates inequality, and they have differential obligations towards groups in vulnerable situations.

A. Background and Context

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) is the second international tribunal to issue an advisory opinion (AO) on States’ international climate change-related obligations, and it will not be the last. The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) delivered the first such opinion last year, and two additional AO proceedings remain pending before the International Court of Justice (coming soon) and the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights. Although AOs lack the binding force of judgments, they carry significant legal weight as they provide authoritative interpretations of the applicable law. This is especially true within the Inter-American System of Human Rights where domestic authorities must consider the Court’s interpretation of law in the execution of their official acts, including in relation to national legislation and policies.

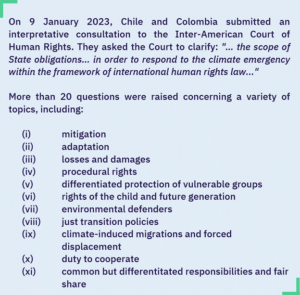

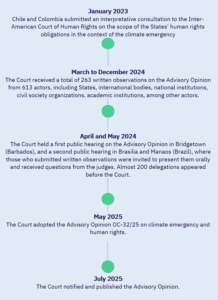

On January 9, 2023, Colombia and Chile submitted to the IACtHR an interpretative consultation (a formal request for legal clarification) under Article 64.1 of the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), with the main purpose of clarifying the scope of States’ obligations in the context of the climate emergency within human rights law. More than 20 questions were posed and they were divided into the following six blocks:

a) States’ obligations derived from the duties to prevent and guarantee of human rights

b) States’ obligations to preserve the right to life and survival

c) Differentiated obligations of States in relation to the rights of children and new generations

d) States’ obligations arising from consultation procedures and judicial proceedings

e) Convention-based obligations of prevention and the protection of territorial and environmental defenders, as well as women, Indigenous Peoples, and Afro-descendant communities; and

f) Shared and differentiated human rights obligations and responsibilities of States.

Like other international tribunals, in exercising its advisory function, the IACtHR is not constrained by the questions submitted and may decide to address only some or rephrase them to provide better assistance in the protection of human rights. Given the number and intricate nature of the questions posed by Colombia and Chile, it was foreseeable that the IACtHR would make use of this discretion, as it ultimately did. Questions were reformulated as follows:

- What is the scope of the obligations to respect and to guarantee rights and to adopt the necessary measures to ensure their exercise… in the case of substantive rights such as the right to life and to health…, personal integrity…, private and family life…, property…, freedom of movement and residence…, housing…, water…, food…, work and social security…, culture…, education…, and enjoyment of a healthy environment…, in relation to the impact or threats caused or exacerbated by the climate emergency?

- What is the scope of the obligations to respect and to guarantee rights and to adopt the necessary measures to ensure the exercise… in the case of the procedural rights, such as access to information…, the right to participation… and access to justice… in relation to the harm caused or exacerbated by the climate emergency?

- What is the scope of the obligations to respect and to guarantee rights and to adopt the necessary measures to ensure their exercise without discrimination… in the case of the rights of children…, environmental defenders, women, Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendant and peasant farmer communities, as well as other vulnerable groups, in the context of the climate emergency?

B. Key Outcomes

(1) The climate emergency as a determining element for the interpretation of States’ obligations

The IACtHR devoted the first substantive part of its AO to examining the so-called climate emergency. In doing so, it reviewed the basics of climate change science as well as the regulatory responses, including litigation. This assessment led the IACtHR to the following opinion:

“Pursuant to the best available science, the present situation constitutes a climate emergency due to the accelerated increase of global temperature, as a result of diverse activities of anthropogenic origin, produced in an unequal manner by the States of the international community, which are having incremental effects and represent a severethreat to humanity and, in particular, the most vulnerable. This climate emergency can only be addressed adequately by urgent and effective mitigation and adaptation actions, and by making progress towards sustainable development with a human rights perspective, coordinated around resilience…”

According to the IACtHR, the climate emergency, part of the ‘triple planetary crisis’, is characterized by the conjunction of three factors: urgency of effective action, severity of impacts and complexity of the required responses.

Regarding the urgency of effective action, the IACtHR referred to the “carbon budget”, the “emission gap” and the “adaptation gap” as developed by the IPCC and UNEP, and underscored the limitations of the current multilateral finance architecture for developing States.

Regarding the severity of impacts, the IACtHR referred to their extreme seriousness —mentioning risk of crossing tipping points— and the exponential increase in the number of people exposed to them. In this context, vulnerability plays a determining role, both for people and ecosystems. It also underscored the need for effective redress as even a global temperature increase of 1,5°C is not safe.

On the complexity of required responses, the IACtHR affirmed that to efficiently address the climate emergency, its structural causes must be addressed, and it requires effective coordination of public and private actors at all levels and in all areas of regulation and public policy, as well as on the articulation of the different branches of international law. It also underlined that the response to the climate emergency must be rooted in the strengthening of the democratic rule of law. Neither the urgency of the measures, nor the seriousness of the impacts or the complexity of the response may serve as justification for undermining democratic systems

This climate emergency constitutes a determining factor in the interpretation of States’ obligations, supporting, for instance, the recognition of an ‘enhanced due diligence’.

(2) General obligations in the context of the climate emergency

States have general obligations under the ACHR and the San Salvador Protocol, including: (a) to respect rights, (b) to guarantee rights, (c) to ensure the progressive development of economic, social, cultural and environmental rights; (d) to adopt domestic law provisions, and (e) to cooperate in good faith.

The obligation to respect rights (art. 1.1 ACHR) means that, in the context of the climate emergency, States must refrain from conduct that undermines measures necessary to protect human rights against climate impacts. This includes refraining from the adoption of regressive measures or practices that results in the unequal or discriminatory enjoyment of human rights.

The obligation to guarantee rights (art. 1.1 ACHR), in the context of climate emergency, requires the totality of State powers to be coordinated — both internally and internationally — so as to protect human rights. Notably, this obligation also encompasses the duty to prevent private actors from impairing the enjoyment of human rights.

According to the IACtHR, this obligation requires States to adopt all the appropriate measures to reduce the risks arising from the degradation of the global climate system and from the exposure and vulnerability to its effects. This duty to prevent is supplemented by the precautionary principle.

The Court clarified that this requires State due diligence, which must be proportionate to the level of risk of harm. Given the climate emergency, States must act with enhanced due diligence to comply with the duty of prevention derived from the obligation to ensure rights.

The level of enhanced due diligence that is to be applied in a specific case depends on the level of risk, the required measures, and the vulnerability of the victims. It entails, among other relevant aspects: (i) the identification and assessment of risks; (ii) the adoption of proactive and ambitious preventive measures to avoid worst-case climate scenarios; (iii) the use of the best available science in the design and implementation of climate action; (iv) the integration of a human rights perspective in the formulation, implementation and monitoring of all climate-related measures; (v) the monitoring of the effects and impacts of the measures adopted; (vi) the strict compliance with obligations under procedural rights; (vii) transparency and continued accountability for State action on climate; (viii) adequate regulation and oversight of corporate due diligence; and (xi) enhanced international cooperation, particularly in relation to technology transfer, finance, and capacity building.

The obligation to adopt measures to ensure the progressive development of economic, social, cultural and environmental rights (art. 2 and 26 ACHR; 1 San Salvador Protocol) includes two related obligations: to adopt progressive measures and to adopt measures with immediate effect. The former translates into a duty to move towards the full realization of rights and includes a duty of non-regression. The latter requires the adoption of effective measures to ensure non-discriminatory access to the benefits of rights.

The obligation to adopt domestic law provisions (art. 2 ACHR and 2 San Salvador Protocol) requires States to adopt the necessary measures to give effect to the rights and freedoms protected. This obligation requires, on the one hand, the elimination of any norms and practices that result in violations of rights, and, on the other hand, the adoption of norms, and the development of practices, aimed at the effective observance of rights. Compliance with this obligation implies ensuring the existence of an adequate domestic legal framework to address both the causes and consequences of climate change.

Finally, the obligation to cooperate in good faith — grounded in various international and regional legal sources — entails, in the context of the climate emergency, the exclusion of evasive, regressive or merely declaratory conduct that frustrates the effective realization of the rights and principles enshrined in the relevant treaties. This obligation is not limited to situations involving transboundary harm; it is particularly relevant in contexts where the international community pursues common objectives and faces collective challenges. In this context, the obligation to cooperate must be interpreted through the principles of equity and of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.

Notably, the IACtHR emphasized the obligation of States to cooperate in promoting an open and advantageous international economic system, particularly for developing countries, thereby enabling them to better address climate change. According to the IACtHR, the obligation to cooperate also entails: (i) financial and economic assistance to the least developed countries to contribute to just transition; (ii) technical and scientific cooperation; (iii) mitigation, adaptation and remediation that may benefit other States; and (iv) the establishment of international forums and the formulation of collaborative international policies.

In addition to these general obligations, the IACtHR specified that, in the context of the climate emergency, States are also bound by obligations derived from specific substantive and procedural rights. Before addressing these specific obligations, the IACtHR introduced a series of notable and markedly progressive developments as part of its analysis of the right to a healthy environment.

(3) The recognition of Nature and its components as subjects of rights

The first of these developments is the IACtHR’s support — albeit by a narrow majority of four votes to three — for the recognition of Nature and its components as subjects of rights. This idea was initially introduced in an earlier AO (AO-23/17) when the Court clarified the contours of the right to a healthy environment.

Here, the IACtHR affirmed that:

“Recognition of Nature and its components as subjects of rights constitutes a normative development that permits reinforcing the protection of the long-term integrity and functionality of ecosystems, providing effective legal tools to confront the triple planetary crisis, and facilitating the prevention of existential damage before it becomes irreversible. This concept represents a contemporary expression of the principle of the interdependence between human rights and the environment, and reflects a growing tendency at the international level aimed at strengthening the protection of ecological systems in the face of present and future threats…”

Based on this understanding, States are not only required to refrain from actions that cause significant environmental harm but must also adopt measures aimed at ensuring the protection, restoration and regeneration of ecosystems.

(4) A novel “jus cogens” norm

A second noteworthy development is the recognition — once again by a narrow majority of four to three — of the prohibition of conduct that may irreversibly affect the interdependence and vital balance of the common ecosystem that makes the life possible as a novel jus cogens norm, meaning it is of such legal importance that no State may violate it. The reasoning of the majority may be summarized as follows.

First, there is global consensus on the reality of existential risks and that individual actions and behaviours can irreversibly harm balance of the shared ecosystem that sustains life on the planet. Anthropogenic contribution to climate change one such behaviour, demanding universal and effective legal responses.

Second, it is indisputable that the balance of the common planetary ecosystem is a prerequisite — a precondition, or “sine qua non” — for the present and future habitability of the planet and, consequently, for the protection and continued enforceability of all fundamental rights safeguarded under international law. It would therefore be logically inconsistent not to prohibit conduct that has an irreversibly harmful impact on the vital balance of our shared planetary ecosystem.

Third, this norm is grounded in general legal principles – especially the principle of effectiveness, which ensures that legal obligations are interpreted in a way that makes them work in practice. If one obligation depends on another, both must be recognised.

Fourth, patterns in State behaviour, international treaties, UN Resolutions, and court decisions point to growing legal support for a clear rule: irreversible environmental harm must not be allowed..

According to the IACtHR’s majority, the recognition of this novel jus cogens norm: (a) is necessary —and not merely convenient or desirable— for the effective fulfilment of obligations already codified by international human rights law; (b) has a solid basis in general principles of law, fundamental human rights and a growing consensus within the international community; and (c) is not arbitrary, but rather grounded in broad and sound legal considerations, consistent with existing law, and contributes to the effectiveness of established norms.

In sum, IACtHR’s majority argued:

“…the principle of effectiveness added to the considerations of dependence, necessity, the universality of the underlying values and the fact that there is no conflict with current law, forms the legal grounds for recognition of the peremptory prohibition to generate massive and irreversible damage to the environment, and it contributes to compliance with existing obligations recognized by international law. Therefore, and given the nature of jus cogens norms, the Court finds that all States should [must] cooperate to put an end to conduct that violates the prohibitions derived from peremptory norms of general international law protecting a healthy environment.”

In the original Spanish version, the verb “deben” (must) is used here, rather than “deberían” (should). Indeed, the IACtHR uses the verb “deberían” only once, in para. 555. In order to preserve the normative tone of the original version, this brief consistently translates “deben” as “must”, regardless of whether the official English translation renders it as “should”. The working language of the adoption of the Opinion was Spanish.

(5) The right to a healthy climate is included in the right to a healthy environment

The third notable legal development is the recognition, by a majority of the IACtHR (five votes to two) of a right to a healthy climate as a component of the right to a healthy environment. The recognition of a right to healthy climate did not require the IACtHR to identify any new normative foundation beyond that of the principal right.

Being a derivative right, it shares the core features of the right to a healthy environment and includes both individual and collective application. In its collective application, it protects the collective interests of present and future generations of humans and other species in preserving a climate system capable of sustaining their well-being. Entitlement to this right rests with all those who share this collective interest. Accordingly, measures taken to prevent, cease, or remedy a violation of this right must simultaneously benefit present and future humanity, as well as Nature as a whole.

As regards the inter-generational element of this right, the IACtHR observed that States must ensure an equitable distribution of the burdens of climate action and climate impacts (taking into account their contribution to the causes of climate change and their respective capabilities). Such distribution must avoid imposing disproportionate burdens on both future and present generations:

“The former may occur if, for example, climate action is unjustifiably postponed, leaving the damage and cost to future generations. The latter would happen if, for example, the costs of the energy transition are allocated without taking into account the vulnerability of certain groups of the population today”.

As regards its ecocentric nature element, the IACtHR emphasized that its protection reaffirms the need for a holistic understanding of the many interactions that sustain life, and calls for recognising humanity as just one more manifestation of Nature’s interdependent network.

As part of this holistic understanding, the IACtHR noted a reciprocal interdependence between climate stability and a stable ecosystem: the protection of the global climate system requires safeguarding the integrity of ecosystems and the living and non-living components that make up and sustain them, while the preservation of climate conditions compatible with life is essential to maintain the balance and functionality of these ecosystems.

“This reciprocal interdependence… reinforces the need for integrated legal approach, capable of uniting the protection of human rights and the rights of Nature within a legal framework coherently aligned with the harmonious interpretation of the pro persona and pro natura principles.”

In turn, in its individual dimension, the right to a healthy climate protects each individual’s right to live in a climate system free from dangerous anthropogenic interference. A violation would occur when the State’s failure to comply with its obligations to protect the global climate system also leads to direct harm to the individual rights of one or more persons. In such cases, States have the international responsibility to provide full reparation for the damage caused to the individuals.

(6) The specific obligations derived from substantive rights in the context of the climate emergency

a. The obligations derived from the right to a healthy climate

aa) Regulation

First, States must define an appropriate mitigation target that reflects the principles of progression and common but differentiated responsibilities. This duty applies unequivocally to all Organization of American States (OAS) Member States —notably including the United States— and the failures of other States to comply with their international obligations cannot be invoked as justification for inaction.

Using the 1,5°C target a minimum baseline, rather than an endpoint, for determining each State’s mitigation target, targets must be determined on the basis of considerations of justice, including those derived from the principles of common but differentiated responsibilities and intra- and intergenerational equity. Accordingly, the magnitude of mitigation to be undertaken by each State must be established according to (i) its current and cumulative historical contribution to climate change, (ii) its capacity to contribute to mitigation measures, and (iii) its specific national circumstances.

In any case, — the IACtHR observed — the mitigation target must lead to carbon neutrality, be as ambitious as possible with built in progression and be enshrined in legally binding regulation.

Second, States must formulate and uphold a human rights-based strategy to achieve the mitigation target. Both the formulation and implementation of such a strategy must include enhanced due diligence, which demands compliance with certain procedural and substantive requirements.

Here, the IACtHR drew attention to the difficulty of satisfying the standard of enhanced due diligence through measures involving technologies whose effects are not entirely proven. It underscored that States must consider, in their regulation efforts, activities and sectors that generate emissions both within and beyond their territory. The IACtHR addressed aspects related to just transition connected to the protection of biodiversity, Indigenous Peoples and economically disadvantaged groups, including the need to protect human rights in the context of rare and critical minerals extraction.

Finally, the IACtHR highlighted the State duty to ensure coherence between their domestic and international commitments, and their mitigation obligations. States must pursue a coherent international policy — particularly in the areas of foreign investment, finance and international trade — and ensure that public funding and incentives for GHG-emitting activities are conditional on strict compliance with national mitigation policies.

Third, referring to the UN Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations, the IACtHR affirmed a State duty to regulate corporate conduct.

States must (i) call upon all companies registered or operating within their jurisdiction to take effective measures to combat climate change and related human rights impact; (ii) adopt legislation requiring companies to carry out human rights and climate-related due diligence across their entire value chain; (iii) require public and private companies to disclose, in an accessible format, the GHG emissions of their value chain; (iv) require companies to take measures to reduce such emissions throughout all their operations; and (v) adopt a set of standards to discourage greenwashing and undue influence in political and regulatory domains, and support human rights defenders.

The IACtHR held that States must establish enhanced climate-related obligations for companies, based on their current and historical contributions to climate change, and in line with the polluter pays principle. Regulation in this area should consider the role of transnational corporations, and enable the attribution of legal responsibility to parent or controlling companies for emissions from subsidiaries or controlled entities.

Finally, States must review their existing trade and investment agreements and investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms to ensure that these instruments do not limit or restrict their efforts on climate change and human rights.

bb) Mitigation monitoring and supervision

In accordance with the standard of enhanced due diligence, States must strictly monitor and control public and private activities that generate GHG emissions. At a minimum, this duty applies to activities like exploration, extraction, transport and processing of fossil fuels; cement manufacturing; and agro-industrial activities.

To fulfil this obligation, States must have robust and independent judicial, quasi-judicial or administrative mechanisms in place, with sufficient staff, resources and technical capacities. States must monitor progress towards the national mitigation target and issue the necessary recommendations to ensure effective compliance. Furthermore, States retain the duty to investigate, prosecute and sanction non-compliance by corporations, as well as acts of corruption.

cc) Climate impact studies

The IACtHR determined that environmental impact studies (EIS) must explicitly include an assessment of the potential effects on the climate system, particularly, of projects with a high risk of generating significant GHG emissions. States must identify which projects require the prior approval of a climate impact assessment and in such cases, the EIS must contain a distinctive mandatory section determining the climate impact.

Regulations governing climate impact assessment must be clear on: (a) the activities and impacts to be examined; (b) the procedure for assessing the climate impact; (c) the responsibilities and duties of the project’s proponents, the competent authorities and the decision-makers; (d) the manner in which the results of the assessment will inform the decision; and (e) the steps and measures to be taken in cases of non-compliance.

Studies must include specific content that considers the nature and magnitude of the project, its potential impact on the climate system, and a contingency plan and mitigation measures if required. In compliance with the standard of enhanced due diligence, States must carefully assess the approval of activities that may cause significant harm to the climate system. This assessment must take into account the best available science, the mitigation strategy and target, and the irreversible nature of the climate impacts.

b. Additional obligations derived from the right to a healthy environment

The IACtHR identified additional obligations related to the protection of Nature and its components, and the progressive advance towards sustainable development.

First, States have a set of obligations related to the identification of resilience challenges; the protection of the affected ecosystems; and the implementation of strategies to protect particularly susceptible ecosystems; among others.[1]

Second, States must promote measures aimed at tackling the structural circumstances that have led to its emergence.[2] States must immediately ensure the existence of a sustainable development strategy and must progressively adopt measures to implement it.[3]

c. Obligations derived from other rights adversely affected by climate impacts

Even if mitigation measures are successful, the best available science leaves no doubt about the inevitability of multiple climate impacts on natural and human systems, with an extraordinary potential to affect human rights. States are obliged to take measures that avoid or reduce such impacts to the greatest extent possible, in accordance with the enhanced standard of due diligence. These measures are qualified, under the international climate regime, as climate adaptation.

According to the IACtHR, as part of their duty to ensure human rights, States have an immediately enforceable obligation to define and keep their national adaptation plan up to date —including a goal and a strategy. The adaptation plan must be designed to achieve its goal and include all necessary measures to prevent and mitigate climate change-related human rights impacts to the greatest extent possible in accordance with a standard of enhanced due diligence.

Adaptation goals and plans must establish short, medium and long-term measures that respond adequately to immediate needs, and also to the structural causes of vulnerability.

Furthermore, adaptation plans must be based on the best available science and be designed in a way the minimise negative side effects on communities and ecosystems, and where insufficient, States must ensure and restore the rights of affected individuals.

In addition to these general rules governing adaptation action, the IACtHR observed that adaptation responses must be defined according to the particular risks to each right and referred to specific obligations emerging from the protection of the following rights: life, personal integrity and health; private and family life; private property and housing; freedom of residence and movement; water and food; labour and social security; culture; and education.

The IACtHR identified further duties regarding, among others: the improvement of infrastructure and capacity of health systems; family unity, unaccompanied children and resettlement in climate-related displacement and migration; real state speculation and social housing programmes; domestic and inter-state prevention and management of forced migration and displacement, including creation of migratory categories which can provide protection against refoulement; water and food security; climate risks into occupational safety and just transition in labour; protection of culturally significant sites and cultural and natural heritage, including Indigenous heritage; and resilience of educational infrastructure and climate change education.

(7) The specific obligations derived from procedural rights in the context of the climate emergency

The IACtHR characterised procedural rights as an essential condition for both the legitimacy and effectiveness of climate action. The Court drew a clear link between procedural rights and democracy, finding that it is essential that States ensure the full respect of procedural rights, under the standard of enhanced due diligence. This standard entails not only the enshrinement of these rights, but also the strengthening of States’ technical and legal capacities.

In addition to the three classic pillars —access to information, public participation and access to justice — the IACtHR identified two additional rights of relevance in the context of the climate emergency: the right to science and the recognition of local, traditional and Indigenous knowledge and the right to defend human rights.

In developing the specific procedural obligations, the IACtHR relies —in addition to its previous rich jurisprudence— on several international and regional instruments, including the Bali Guidelines, the Escazú Agreement, the Aarhus Convention and European Union Directives. The influence of the Escazú Agreement is particularly remarkable.

a. The right to science and the recognition of local, traditional and indigenous knowledge

According to the IACtHR, the right to science is protected by various instruments of the Inter-American System, as well as the International Pact on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and encompasses the access to the benefits of scientific and technological progress, as well as the opportunities to contribute to scientific activity, without discrimination. This right constitutes a key means for effective access to fundamental rights, as well as one of the foundations of public decision-making.

The IACtHR observed that, alongside scientific knowledge, other forms of knowledge coexist such as local, traditional and Indigenous knowledge. Taking this a step further, the right to science encompasses not only access to the benefits derived from science in the strict sense, but also from these alternative systems of knowledge. Accordingly, States also have obligations concerning the protection of such knowledges.

Finally, the IACtHR established that, in order to determine what constitute the best available science, States must take into account several criteria related to its up-to-date nature, as well as the methodologies and processes through which it produced, disseminated, and validated. Here the IACtHR emphasises that the best available science on climate change is currently compiled in the IPCC reports.

b. The right to access information in the context of the climate emergency

The IACtHR found three specific State duties that derive from this right: (1) to produce information; (2) to disseminate and facilitate access to information; and (3) to adopt measures against disinformation.

These duties relate to and include: the establishment of early warning systems, the production and dissemination of data necessary to establish, implement, update and monitor mitigation and adaptation goals and strategies; corporate reporting duties; transparency of climate action-related funds; free access to climate information; dissemination of information in the event of imminent threats; and measures against false or misleading climate-related information.

c. The right to public participation in the context of the climate emergency

The IACtHR reaffirmed that States must ensure processes for meaningful, broad and non-discriminatory participation in decision-making that may affect the climate system, as well as the rights of communities.

Public participation in climate matters extends to decision-making processes concerning mitigation goals and strategies, adaptation and risk management plans, financing, international cooperation and redress for damages. In addition, States must cooperate to ensure public participation in climate-related decision-making at the regional and international levels.

Among other requirements, States must guarantee the public the possibility to effectively influence the design of and decision on projects and policies. Consequently, the results, consensus and decisions of participatory processes must be central elements in motivating the decisions of the authorities, who must explain how they have taken these inputs into account.

d. The right to access to justice in the context of the climate emergency

The IACtHR also underscored the essential nature of access to justice in the context of the climate emergency and established a notably broad and detailed set of duties and conditions applicable to various stages of the litigation process. As such, these provisions are undoubtedly relevant for the deployment of climate litigation in the region.

These include: (i) the provision of adequate institutional resources, such as training for legal operators and the creation of specialised bodies; (ii) the application of the “pro actione” principle, i.e., the interpretation most favourable to access to justice must always prevail; (iii) the processing and resolution of cases within a reasonable time; the establishment of procedural mechanisms that allow for broad forms of legal standing (collective, public or popular standing), and the flexible assessment of the interest to act; the adoption of alternative probative standards, such as the reversal of the burden of proof, as a response to complexities of climate cases and asymmetry in the control and access to evidence; and the provision of effective mechanisms to enable full reparation.

e. The right to defend human rights and the protection of environmental defenders in the context of the climate emergency

Building upon its previous jurisprudence, the IACtHR articulated a comprehensive and detailed set of State obligations derived from the right to defend human rights and the environment in the context of the climate emergency. This development was grounded in the fact that environmental defenders perform an essential function and, as such, are owed a special duty of protection by the State.

This special duty includes State obligations to recognise, promote and guarantee their rights; guarantee a safe and favourable environment to perform their activities; and investigate and punish any attack on them. Ultimately, it imposes an enhanced obligation to implement appropriate public policy and to adopt the pertinent domestic legal provisions and practices to ensure the free and safe exercise of these activities.

In the context of the climate emergency, environmental defenders are at heightened risk, including online violence, arbitrary detentions and strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPP). More broadly, environmental defenders face violent attacks and threats to their families, enforced disappearances, unlawful surveillance, travel bans, blackmail, sexual harassment, judicial harassment and the use of force to dispel peaceful protests. Women defenders, journalists, members of rural communities, Afro-descendants and Indigenous Peoples face even greater risks.

The IACtHR identified a series of specific State obligations concerning the protection, monitoring and punishment of attacks, the dismantling of the structural causes of violence, as well as the adoption of national programmes that include training and education aimed at State agents, the general public, and the media. In light of the collective impact of violence against environmental defenders, States must fulfil their obligation to investigate, prosecute and punish crimes against them in accordance with the standard of enhanced due diligence.

Finally, the IACtHR addressed the criminalisation of environmental defenders by the undue use of law, judicial harassment, arbitrary detention, and convictions with disproportionate sentences. States must review regulations and procedures, as well as promote special education and training for police and judicial authorities.

(8) The differential obligations towards groups in vulnerable situations

The IACtHR dedicated the Opinion’s final section to the differential obligations owed to groups in vulnerable situations. The Court found a special duty of protection regarding actions of third parties that, under the State’s tolerance or acquiescence, create, maintain or favour discriminatory situations.

In other words, it is not sufficient for States to abstain from violating rights, they must adopt measures tailored to the particular protection needs of the right-holders. States incur international responsibility when, in the face of structural discrimination, they fail to adopt specific measures regarding the particular situation of victimization in which vulnerability arises.

Climate change generates extraordinary and increasingly severe risks for the human rights of certain groups whose vulnerability is increased by the convergence of intersectional and structural factors. To ensure real equality in the enjoyment of rights amid the climate emergency, differential measures are required in all State actions. While such measures must be shaped by the particular risks identified by each State, the existence of shared patterns of vulnerability gives rise to corresponding specific obligations.

The IACtHR identified differential protection measures that States must adopt for the protection of children; Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, Afro-descendants, peasant farmers and fishermen; and, in the context of climate disasters, women, older persons, persons with disabilities, and gender-diverse persons. The Court observed that there are other groups especially affected by climate change that do not correspond to categories traditionally protected and that the State must identify their needs and adopt specific measures for them.

Finally, the IACtHR noted that climate change is a determining factor that aggravates inequality and multidimensional poverty. It affirmed that States must design and implement policies and strategies to ensure people living in poverty have access to the goods and services necessary for a dignified life in the context of the climate emergency, and to progressively eradicate the structural causes of their vulnerability. Where relevant, these policies must be included in climate mitigation and adaptation plans and strategies. A just climate transition must not deepen poverty but instead be used as an opportunity to overcome it.

C. Climate change litigation implications

Three key elements highlight the main implications of the IACtHR’s AO for climate change litigation more broadly.

First, the effects of IACtHR’s AOs on the legal systems of the States of the region. The IACtHR addressed this point explicitly in the Opinion:

“…the Court recalls that, when deciding litigations and legal issues that may arise in the context of the climate emergency, the competent authorities should [must] conduct due control of conventionality based on the standards developed by the Court in its case law and, in particular in this Advisory Opinion, to ensure adequate protection of human rights. These standards also result from the American Declaration, the OAS Charter, and the Inter-American Democratic Charter and are, therefore, applicable in all member countries of the inter-American system.” (para. 560)

Although AOs do not carry the same binding force as judgments, they have significant legal weight and effects as authoritative interpretations of the applicable legal framework by the principal judicial body of a system. The Court has stated that, under the doctrine of control of conventionality, domestic authorities—including judges—must ensure that national laws and practices align with the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR) and broader human rights standards. This includes following the IACtHR’s interpretations, whether made in judgments or AOs, even if the State wasn’t involved in the original case.

As confirmed after the publication of Advisory Opinion OC-32/25, domestic authorities must now assess whether their laws and policies meet the standards it sets. This is likely to be tested and clarified through litigation across the region. A key question remains: how actively will domestic courts apply this duty, and how will they manage the many detailed standards laid out by the Court?

In turn, domestic authorities of OAS member States that are not parties to the ACHR are also affected by Aos.. According to previous IACtHR’s jurisprudence, AOs provide them with legally relevant sources and interpretative guides. In this regard, and with reference to the last sentence of the quoted fragment, it is worth recalling that the OAS Charter is a binding treaty, and that, according to the IACtHR, the American Declaration constitutes the definitional source of the human rights referred to in the Charter, thereby producing legal effects.

A second element that will have implications for climate change litigation is the confirmation that the IACtHR’s approach to extraterritorial jurisdiction in cases of transboundary environmental harm —established in the AO OC-23/17— is applicable to climate change:

“…climate damage is, by its nature, transboundary… and… States must provide prompt, adequate and effective redress to individuals and States that are victims of transboundary harm resulting from activities carried out in their territories or under their jurisdiction, when there is a causal link between the damage caused and the act or omission of the State of origin in relation to activities in its territory or under its jurisdiction or control. Consequently, the Court stresses that the guarantee of access to justice involves the legal standing of people and entities that do not reside in the State’s territory.”

This opens the door to diagonal climate litigation —i.e., cases in which individuals or groups under the territorial jurisdiction of one State bring claims against another State for transboundary climate harm— and to corresponding extraterritorial climate legal standing (and victim status). In this respect, the IACtHR stressed that domestic legal systems must ensure access to justice, and particularly legal standing, for people and entities not residing in the State’s territory. This will arguably lead to new and further climate litigation in the region. It is noteworthy that, while this approach has been endorsed by the Committee on the Rights of the Child, it was rejected by the European Court of Human Rights, raising important questions about the implications of this recognition in terms of global climate justice.

A third and final element concerning the implications of the Opinion for climate change litigation is the adoption of a broad set of standards on access to justice and, in particular, on the procedural and institutional barriers that — as the IACtHR noted — may negatively affect this right in climate-related cases, given their special features. As outlined above, the IACtHR set out standards related to institutional shortcomings and cost barriers; time constraints; broad and flexible legal standing — including collective actions —; evidentiary hurdles; and the provision of adequate remedies.

All these standards — which align with those of the Escazú Agreement — will positively influence the deployment of climate litigation, as well as its likelihood of success and impact on climate governance. In other words, if properly implemented, they may help pave a gentler path forward for climate litigation in the region.