In this case, the Court:

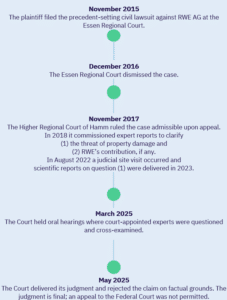

- Found the claim to be valid on its face, i.e. that the claimant’s statement on facts and arguments on RWE’s legal accountability for the alleged property interference were considered coherent and legally capable of substantiating the asserted claim, provided that the alleged facts are true;

- Thus, clarified that, in principle, major emitting companies can be held accountable under German civil law for climate-induced damage risks beyond borders;

- Ultimately, dismissed the claim on factual grounds based on the evidence before the Court that there is a lack of sufficient risk to the claimant’s property;

- Relied on a comprehensive evidentiary procedure, including an on-site visit of the parties, however,

- Finally, did not assess climate attribution science, as the claim did not meet the preliminary evidentiary question regarding the impending interference with property.

(1) Context

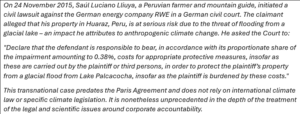

RWE has been active as a major energy producer since the early 20th century and is headquartered in Germany. Through coal-fired power generation, it has released large amounts of greenhouse gases (GHGs) under the applicable laws and permits. The claimant is the owner of a residential house in Huaraz, a Peruvian city in the Andes, about 25 km from the Palcacocha glacial lake, and had already experienced partial destruction of his home due to a previous flood wave. Over the last few decades, the volume of the glacial lake has increased significantly, requiring increasingly extensive protective measures.

As part of the proceedings, the Court obtained expert opinions and conducted a site visit to view the location at issue in the case.

(2) Formal Decision

The Court confirmed the admissibility of the claim. However, it ultimately found the claim to be unfounded in substance.

Importantly, the Court determined that the claimant’s legal argument was coherent. This means that the claim would have been legally substantiated if the underlying facts had been proven true. The lack of merit of the claim thus results from a divergence in the factual basis according to the evidence, not from legal errors.

(3) The Claim is Admissible

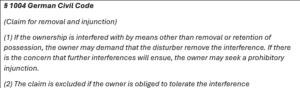

While the international jurisdiction of the German Court was not particularly problematic, the Court – due to objections raised by the defendant – also addressed whether the alleged impending interference with property resulted in a current legal relationship between the claimant and defendant. Under German procedural law, this requirement is intended to prevent purely theoretical or future legal conflicts from reaching the courts. The Court clarified that the GHG emissions by the defendant already formed the basis for potential future legal obligations under § 1004 of the German Civil Code (BGB), thus establishing a current legal relationship.

The Court further clarified the claimant’s legitimate interest in a judicial determination: not only must the liability question be clarified as soon as possible, but also that the uncertainty regarding the impending statute of limitations on additional claims should be removed. Also of interest is the Court’s brief note that the fact the claimant is demanding only a minimal share of the costs from the defendant does not constitute an abuse of rights. Finally, regarding the requirement for a sufficiently specific claim, the Court stated this requirement is fulfilled even if the claim does not specify “appropriate protective measures”.

(4) German Civil Law Applies

The Court rejected to the defendant’s argument that German civil law is not applicable in this case. The applicability of German law is also based on the so-called “place of action rule,” given the defendant’s conduct (emission activities) has been ongoing for many decades.

(5) The Injunction Claim is Coherent

Over more than 50 pages, the Court explained why the claimant’s claim is legally sound and why the defendant’s objections do not hold up legally. The Court conducted a deep legal analysis based on German civil law doctrine and made far-reaching legal evaluations on the legal responsibility of major emitters. The judgment mainly refers to existing German case law but also makes differing assessments in some places, justified by the particularities of climate change and supported by extensive legal scholarship.

It first clarifies that the claim for injunctive relief under § 1004(1) BGB is applicable to the context of climate change and this specific case. The claimant can use it to demand the elimination of an impending impairment to property by the disturber. The aim is not to restore it to its previous state (as in tort law), but to ensure that the effect of the disruptive activity is rendered ineffective for the future. This could be achieved through measures at the glacial lake or on the claimant’s property. According to the Court, it does not matter that RWE, if convicted, would have no choice regarding which measures to take.

Also notable is the Court’s clarification that under German property law, the fact that the claimant lives far away from the source of the interference (the defendant’s power plants) does not bar the claim. Direct proximity is not a requirement.

(6) RWE is Responsible for the Alleged Property Interference

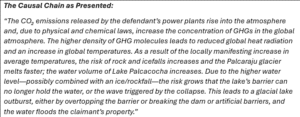

One of the most far-reaching determinations by the Court is that, based on legal standards, the released CO₂ emissions causally contributed to the alleged interference with property, and that this interference is attributable to RWE.

The Court applies legal (not scientific) causality based on the conditio sine qua non formula (a legal “but-for” test: but for the condition, the result would not happen), limited by the theory of adequacy (extraordinary circumstances are excluded).

It first rejects various arguments by the defendant that emissions were caused by subsidiaries and not directly attributable to RWE as the parent company.

Then it makes another broad statement relevant to other climate cases:

“Based on these principles, the adequate causality of the defendant’s contribution must be affirmed, since an optimal observer in the role of the defendant could have recognized as early as the mid-1960s that a significantly increased industrial CO₂ output would lead to global warming and the consequences alleged by the claimant.”

Thus, the Court is convinced that energy producers (and other major emitters) must have anticipated the consequences of their emissions since at least the 1960s, based on Keeling’s data (1958) and other reports – well before the UNFCCC.

The Court also rejects the defendants’ objection that RWE’s contribution is not significant. It points out that significance must be assessed in relation to other contributors. RWE’s 0.38% share of all industrial CO₂ emissions is not insignificant, especially considering no single emitter exceeds 3.6% of global emissions.

It is also significant that the Court finds RWE not only indirectly but directly responsible for the emissions, including those of its subsidiaries. Legally, RWE directly caused the threat to claimant’s property – even if the causal chain ultimately ends in a natural event (the glacial lake outburst). The Court explains why climate change requires a distinct legal assessment and cannot be compared with precedent-setting cases dealing with natural events. Climate change is not an event independent of human influence. Crucially, the physical processes are neither accidental nor too complex to be addressed legally.

The Court adds a further legal clarification: Unlike tort claims, it does not matter whether RWE violated a legal obligation in causing the interference. This restrictive criterion is not needed because the climate-related impairment is not a purely natural event, but stems from human activity and the causal chain is foreseeable.

(7) Cumulative, Distant, and Long-Term Damage Are a Matter for Civil Courts, Not Just Politics

The defendant referred to a Federal Court of Justice precedent regarding acid rain and forest dieback to question whether complex damage can be attributed to a single emitter. The Court, citing academic literature, explains why forest damage is not comparable to climate damage and why the precedent does not exclude emitter liability.

The Court also addresses the judiciary’s role in addressing climate change. It explicitly states there is no legal basis to defer climate liability cases solely to political instruments. It also dismisses concerns of judicial overload, as legal standards of adequacy and significance apply. It illustrates this by calculating an average German citizen’s contribution to climate change at 0.0000000628%.

The Court further rejects the idea that the claimant must first or only sue the largest contributor.

(8) Illegality Depends on Harmful Result

RWE argued its emissions were lawful under permits and laws. This is often cited in legal literature to exclude civil liability for legal conduct. The Court, however, makes clear that the relevant claim depends on whether the result of the action (here, the property threat) violates legal norms. It interprets the applicable provision accordingly and refers to established case law.

(9) No Duty to Tolerate Imminent Climate Damage

Under German law, certain interferences must be tolerated if they are negligible or justified by a neighbourly relation. The Court reviews all potential arguments for a duty to tolerate. It concludes that partial destruction of the house is not negligible. It rejects a neighborhood-based duty given the geographic distance. It also notes that the claimant could not have challenged RWE’s emission permits early on.

The Court adds that participation in emissions trading and possession of permits does not imply a duty to tolerate emission impacts. Public law regulation does not legalize emissions in full. Civil liability remains unless explicitly excluded by law.

The Court also addresses the balance between public interest in energy generation and liability. It allows that a duty to tolerate may exist in rare cases of public interest, but such a duty would not justify leaving a property owner without recourse.

Finally, it rejects the argument that the claimant bears responsibility for his risk because he acquired the property knowing the danger. The Court finds RWE’s reasoning insufficient and any contributory fault by the claimant implausible.

For similar reasons, it denies contributory negligence: the claimant did not participate in causing the danger, and it would be unfair to relieve RWE of liability due to the claimant’s property acquisition.

(10) Claim is not Time-Barred

The Court finds that ongoing emissions and recurring interference reset the statute of limitation. It also explains why the claimant’s lack of knowledge was not negligent, and thus the claims are not time-barred, meaning that the time that has elapsed since the original harmful acts by RWE does not bar the claim.

(11) The Claim is Not Proven in this Case

Over about 40 pages, the Court explains why it finds the claimant failed to prove the property threat.

The Court had to define its own standard for assessing an impending threat. It held that the probability threshold depends on the severity of potential damage. It set a 30-year time frame for assessing the threat, considering longer periods to be too speculative.

The Court’s handling of proof requirements may guide future plaintiffs in strategy and evidence. It emphasized that only site-specific expert analysis is relevant and reviewed the methods used carefully.

Whether baseline risk (e.g., dam failure due to earthquakes) should be deducted from climate risk didn’t need to be resolved, as the claim failed on other grounds.

Ultimately, the Court followed its own appointed expert’s assessment and found the claimant had not proven a serious threat to his property.

In sum, the Court set a high bar for proving climate-related property threats. Its in-depth discussion will likely serve as guidance for future litigation strategies and evidence presentation.

According to the Court, even with additional climate risk factors applied to the 1% figure, the probability is still too low given the high value of the rights at stake.

Importantly, since the proof of likely property damage failed, the Court did not need to address classical climate attribution science. Thus, its judicial application at such a granular level remains untested.

Climate change litigation implications

The case falls under C2LI Scenario 3: an individual sought to hold a private actor liable for its contribution to climate change. The judgment, while rejecting the claim, has nonetheless established important legal signposts for the future of climate litigation globally. Its implications are multi-facetted and arise less from the judgment itself than from the extensive judicial reasoning and the unique nature of the proceedings.

It has shown that civil courts are willing to apply nuisance law principles related to property protection to the global and systemic challenges posed by climate change. This is not self-evident, given the historically local focus of such doctrines and the unprecedented complexity of climate-related harm. The decision by the higher court authoritatively affirms that private law is not categorically unsuited to address the climate crisis and may, under certain conditions, serve as a vehicle for redress and risk internalisation. The judgment is likely to be of particular interest for climate lawsuits in countries where state regulatory responsibility and the actual responsibility of private and state actors diverge. This case demonstrates how actors could be held legally accountable in the absence of climate legislation or regulation.

The Court engaged very thoroughly with various objections raised by RWE, which also play or could play a role in many other proceedings. Crucially, the Court also rejected the notion that a defendant’s relatively small share of global emissions renders legal responsibility irrelevant. It affirmed that even partial contributions can, in principle, give rise to liability, provided that a sufficiently concrete causal link to the harm at issue is demonstrated. This clarification has opened a (narrow) pathway for claimants to pursue private actors for their role in accelerating climate change, even in the absence of specific climate legislation. The logic is preventive: emitters, and those who enable emissions, are now on notice that their conduct may attract legal scrutiny. That deterrent effect is also relevant for financial institutions and service providers who support high-emission business models.

While the claim failed on evidentiary grounds, the Court did not dismiss it as legally unfounded or too remote in theory. This distinction is critical. The outcome demonstrates that climate liability is above all a matter of evidence: success depends on the ability to translate global (climate) science into event-specific, locally situated expert findings that meet the strict standards of civil procedure. Through its detailed reasoning, the Court provided significant insight into critical points of evidentiary presentation. This will likely inform future strategies about the “where” and “who” in climate litigation.

Holding corporations legally accountable for specific property interference risk through climate change was merely considered speculative before this case. In this sense, strategic climate litigation has reached a significant milestone. Although the likely ‘tipping point’ of applying climate attribution science to full its extent in a civil court proceeding has not been reached, there is now a clear outline of how this could look e. The case sharpened the focus on where scientific development and legal strategy must converge. The judgment is not a door-closer, but a precedent-setter.

The proceedings also carry transnational significance. They have demonstrated that courts in the Global North can serve as venues for redress for affected communities in the Global South. This is a step towards reversing the long-standing asymmetry between emitters and victims and will likely strengthen the strategic use of transnational legal remedies. The symbolic and political impact of a Global South plaintiff seeking accountability from a major European emitter in a Northern court should not be underestimated. It has already inspired similar actions (see Asmania et al v Holcim and others) and will likely continue to do so.