Introduction

A perennial issue facing aid-granting authorities is whether the aid applicants are SMEs. A mis-assessment of the SME status can have dire consequences as demonstrated by a Commission decision in May 2025 concerning State aid granted by Germany to sawmill Abalon Hardwood Hessen [AHH] [SA.24030]. The Commission found the aid to be incompatible with the internal market and ordered Germany to recover it [the Commission decision is not yet published in the Official Journal].[1]

In 2007 Germany notified to the Commission two state guarantees and other measures in favour of AHH. The Commission decided in 2008 that the two guarantees did not constitute State aid while the other measures were existing aid.

However, a competitor, Pollmeier, brought an action for annulment before the General Court which held in 2015, in case T-89/09, Pollmeier v Commission, that the Commission erred in its assessment of the two guarantees. Consequently, in 2016, the Commission opened the formal investigation procedure which was concluded 10 years later with a negative decision. Interestingly, also in 2016, an appeal by Pollmeier against the judgment of the General Court was rejected by the Court of Justice in case C-246/15 P, Pollmeier v Commission.

The subject of the 2025 Commission decision is two guarantees concerning an investment loan and a working capital loan.

The SME status of AHH

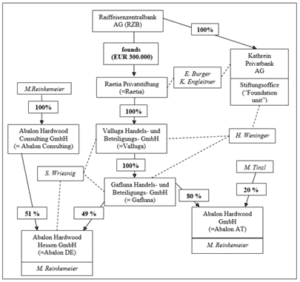

The first issue that the Commission examines is whether AHH was an SME. AHH was a company in a complex web of corporate and personal shareholdings. A diagram showing this web of shareholdings is reproduced below. In the diagram and in the Commission decision AHH is called “Abalon DE”.

[1] The full text of the Commission decision can be accessed at:

https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases1/202523/SA_24030_433.pdf

First, the Commission refers to its SME Recommendation and the interpretation by the Court of Justice of the EU [CJEU]. “(97) The criteria to establish whether an undertaking constitutes an SME are laid down in the SME Recommendation, as interpreted by the Court of Justice. The Court of Justice has in particular recalled that ‘the SME Recommendation must be interpreted by taking into account the reasons for its adoption’”. [The Commission cites extensively the judgments in cases C-110/13, HaTeFo v Finanzamt Haldensleben, C-516/19, NMI Technologietransfer, and C-572/19 P, Ertico – ITS Europe v Commission.]

In paragraphs 98-102, the Commission reiterates the provisions of the Annex of the SME Recommendation [ASME]. Then it recalls that “(103) Article 3(3), fourth subparagraph, of ASME adds that ‘enterprises which have one or other of such relationships through a natural person or group of natural persons acting jointly are also considered linked enterprises if they engage in their activity or in part of their activity in the same relevant market or in adjacent markets.’ In the HaTeFo judgment, on the interpretation of that provision, the Court of Justice held that that provision ‘must be interpreted as meaning that enterprises may be regarded as “linked” for the purposes of that article where it is clear from the analysis of the legal and economic relations between them that, through a natural person or a group of natural persons acting jointly, they constitute a single economic unit, even though they do not formally have any of the relationships referred to in the first subparagraph of Article 3 (3) of that annex. Natural persons who work together in order to exercise an influence over the commercial decisions of the enterprises concerned – which precludes those enterprises from being regarded as economically independent from each other – are to be regarded as acting jointly for the purposes of the fourth subparagraph of Article 3 (3) of that annex. Whether that condition is satisfied depends on the circumstances of the case and is not necessarily conditional on the existence of contractual relations between those persons or a finding that they intended to circumvent the definition of a micro, small or medium-sized enterprise within the meaning of that recommendation.’”

Next, the Commission observes that “(105-106) Abalon DE, in itself or in combination with Raetia, Abalon Consulting, Valluga, Gafluna and Abalon AT, remained below the relevant staff headcount, turnover, and balance sheet thresholds of the ASME and would therefore qualify as an SME. On the other hand, Abalon DE cannot qualify as an SME if RZB is considered as a linked or partner enterprise within the meaning of the ASME. Indeed, RZB itself did not fulfil the SME criteria since its staff headcount (55 000 in 2006) and annual balance sheet (EUR 115 billion in 2006) […] exceeded the respective thresholds of 250 employees and/or EUR 43 million annual balance sheet.”

In other words, the decisive issue is whether RZB was linked to AHH (or Abalon DE).

The first step in determining the relationship between RZB and AHH was to establish the relationship AHH and Gafluna which owned 49% of AHH. That appears not to constitute controlling interest. However, “(112) in accordance with Article 5(2) of Abalon DE’s articles of association, both shareholders (Gafluna and Abalon Consulting) have the right to appoint one managing director each and to remove that person from that function. Since Gafluna can only appoint or remove one out of two managing directors, it does not have the right referred to in Article 3(3), first subparagraph, point (b), of ASME, to appoint or remove a majority of the managing directors. Additional managing directors can only be appointed by the general assembly, in which Gafluna has no majority of the voting rights (see above, recital (111). Therefore, the Commission concludes that the relationship between Abalon DE and Gafluna does not meet the conditions set out in Article 3(3), first subparagraph, point (b), of ASME.”

“(113) Thus, the Commission assesses a possible right to exercise a dominant influence over another enterprise pursuant to a contract entered into with that enterprise or to a provision in its memorandum or articles of association as referred to in Article 3(3), first subparagraph, point (c), of ASME. To establish whether a dominant influence is exercised, the Commission relies on the case-law of the Court in the context of the SME Recommendation. In the HaTeFo judgment, the Court held that ‘the condition that natural persons are acting jointly is satisfied where those persons work together in order to exercise an influence over the commercial decisions of the enterprises concerned which precludes those enterprises from being regarded as economically independent of one another’.”

“(114) It is also useful to refer to the case-law of the Court in the context of the Merger Regulation, which also refers to an exertion of ‘decisive influence’ and is connected to the notion of ‘single economic unit’ used by the Court when interpreting the SME Recommendation. In this context, the Court held, referring to the Commission Jurisdictional Notice, that decisive influence implies ‘the power to block actions which determine the strategic commercial behaviour of an undertaking. Thus, joint control may result in a deadlock situation owing to the power of two or more undertakings to reject proposed strategic decisions. It follows, therefore, that those shareholders must reach understanding in determining the commercial policy of the joint venture […] [and that they] are required to cooperate’.”

Therefore, those that have veto power can exercise a dominant influence because without their consent the company cannot function.

“(115) In the present case, […], both shareholders of Abalon DE have the right to appoint or remove one managing director. Although Gafluna did not make use of this right, Gafluna could have blocked management decisions of Abalon DE, had it appointed a second managing director, in addition to Manfred Reinkemeier, who was appointed by Abalon Consulting. In that case, the two managing directors would collectively represent Abalon DE and take strategic decisions, unless a qualified majority of 2/3 of shares/votes entrusted only one of them with that power. However, such a 2/3 majority cannot be reached against Gafluna, which holds 49 % of the shares.”

“(117) In the light of the above, Gafluna in 2006 could exercise dominant influence over Abalon DE; this derives from the joint control of Gafluna over Abalon DE, through the appointment of senior management and veto rights on strategic decisions on the business policy of Abalon DE. The Commission thus concludes that Gafluna and Abalon DE are linked enterprises within the meaning of Article 3(3), first subparagraph, point (c), of ASME.”

Next, the Commission finds that Abalon AT, Gafluna, Valluga and Raetia were also linked enterprises. The last step is to establish the relationship between RZB and Raetia which owns 100% of Valluga which, in turn, owns 100% of Gafluna (which owns 80% of Abalon AT). In this connection, the Commission, first, notes that Raetia is a foundation founded by RZB. “(123) The Commission notes that, […], under Austrian law, foundations are considered as legal personalities in principle independent from their founder and that the founder has generally no rights vis-à-vis the foundation, its bodies, nor the foundation’s assets (so-called separation principle (Trennungsprinzip) […] However, the Commission assesses the links between the foundation and its founder against the ASME and the related case law of the Union Courts, not against Austrian law.” “(124) In accordance with Article 3(3), first subparagraph, point (b), of ASME, the assignment of rights of appointment indicates that two enterprises are linked. Raetia’s foundation deed creates a governing board of the foundation, composed of three members. […] In accordance with the foundation deed, RZB as founder appointed the first governing board […] for an unlimited period of time. Subsequent members can be appointed by unanimous decision of the foundation’s governing board itself. Until at least 2006, the composition of the foundation’s governing board remained unchanged.”

The Commission concludes that “(125) when the two guarantees were issued in 2006, Raetia’s governing board was composed exclusively of RZB appointees. As RZB was entitled to appoint and did appoint all initial members of Raetia’s governing board responsible for managing its business, the Commission concludes that RZB and Raetia are linked enterprises within the meaning of Article 3(3), first subparagraph, point (b), of ASME.”

I find this conclusion very tenuous. In itself it cannot prove that the appointed board members act on behalf of RZB or to further the interests of RZB, especially given that the board of a foundation acts independently of the founder and that the subsequent members of the board are appointed by the board and not by the founder.

Perhaps for this reason the Commission also examines indirect relationships between RZB and Raetia. “(127) Kathreinbank is a 100 % subsidiary of RZB and is therefore linked to RZB within the meaning of Article 3(3), first subparagraph, point (a), of ASME. Although there was no shareholding links or voting rights between Kathreinbank and the Raetia linked entities in 2006, there are personal links between them that are relevant for the assessment of the qualification as SME”. “(128) In particular, […] there was a certain overlap of personnel in the management and supervisory bodies of Raetia and Kathreinbank […] At that time, the governing board of Raetia was composed of Ernst Burger, Kurt Engleitner and Karl Pistotnik. At that time, Ernst Burger and Kurt Engleitner were also members of the supervisory board of Kathreinbank.” “(129) In addition, […], one of the two managing directors of Valluga and Gafluna, Heinrich Weninger, led the ‘foundation unit’ of Kathreinbank. Finally, Gafluna, Valluga and Kathreinbank had their place of business at the same address when the guarantees were issued.” “(130) In the Commission’s view, which is based on a global assessment of all factual circumstances mentioned above, the overlap in the management between Kathreinbank, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, Raetia, Valluga and Gafluna constitutes links through natural persons within the meaning of Article 3(3) of ASME.”

As a result, the Commission finds that AHH was not an SME. The consequence of this finding is that the safe harbour rates for the calculation of the market premium of guarantees cannot apply to the guarantees granted to AHH, given that the gross grant equivalent of State aid embedded in a guarantee is the difference between the market rate of premium and the premium actually charged.

State aid in the guarantees

The Commission begins its analysis of the guarantees [and whether they conferred an advantage to AHH] by recalling the methodology for calculating the GGE, if any. This methodology, which is explained in paragraphs 144-149, can be summarised as follows:

- State aid is granted at the moment when a guarantee is given, and not at the moment when the guarantee is invoked.

- The market rate of premium depends on the credit rating of the borrower.

- In principle, the GGE is the difference between the market premium and the premium actually charged.

- As a proxy for the market rate of premium, a benchmark can be defined on the basis of premiums paid by comparable companies for comparable transactions.

- Comparable companies are those with a similar probability of default.

With respect to AHH’s probability of default, the Commission takes into account the average of default rates assigned to AHH by two banks. That rate was 1.66%. “(155) On the basis of this average default rate, the credit quality (rating) of Abalon DE in 2006 is in the ‘Ba2’/‘Ba3’ range on Moody’s rating scale, corresponding to the ‘BB’/‘BB-’ range on S&P’s rating scale.” Because guarantee premiums charged to companies with a rating similar to the one of AHH were not available, the Commission established the market price by relying on traded credit default swaps (CDS). It finds that the market rate “(158) is 2.19 % for the working capital loan […] and 2.66 % for the investment loan”.

Next, the Commission calculates the GGE using the default rates of 2.19% and 2.66%. The actual rate paid by AHH for both loans was 1%. For the discounting of future cash flows, it uses the discount rate of 6.36% rate which is equal to the 2006 base rate for Germany [5.36%], increased by 100 basis points according to the 2008 Communication on reference and discount rates. Therefore, “(161) the gross grant equivalent of the aid contained in the investment credit guarantee is EUR 1 380 705 and the gross grant equivalent of the aid contained in the working capital credit guarantee is EUR 129 134, thus an overall aid amount of EUR 1 509 839.”

The Commission also considers whether the GGE can be calculated using an alternative method: the difference between the market rate of interest on the underlying loans without the guarantee and the rate of interest actually charged with the guarantee minus the premium actually paid [paragraph 164]. However, in the end it does not perform that calculation because Germany did not submit any relevant information.

Compatibility

The Commission concludes its assessment by examining whether the State aid is compatible with the internal market. It finds that the investment loan can be compatible but the amount of aid exceeded the maximum permissible for regional investment in an Article 107(3)(c) area. Since AHH was a large enterprise, it could not benefit from the SME bonus. Given that only EUR 180,000 could be legally granted, the excess amount of EUR 1,200,705 is incompatible aid that has to be recovered.

With respect to the working capital loan, the aid embedded in the guarantee was operating aid that could not be granted in an Article 107(3)(c) area, regardless of whether AHH could have qualified as an SME. Therefore, the whole amount has to be recovered.