All individual awards of aid granted to the same project over a three-year period have to be counted together and remain below the maximum allowable aid intensity in relation to the sum of eligible costs.

Introduction

Hungary operates an aid scheme that offers tax credits to encourage regional investment. The scheme has been implemented on the basis of the GBER [SA.39292]. The GBER requires individual notification of aid amounts above certain thresholds. The Commission, in decision SA.49580, assessed an individual award for the extension of an existing establishment.[1]

Hungary proposed to grant regional aid for an initial investment by a large undertaking, BorsodChem, in Kazincbarcika, an area eligible for aid under Article 107(3)(a) TFEU with maximum intensity of 50%. The individual notification threshold for projects in regions with aid intensity of 50% is EUR 37.5 million [see Art 2(20) of the GBER].

BorsodChem is a fully-owned subsidiary of Wanhua Industrial Group [WIG], a Chinese company, with turnover of EUR 4,757 million and more than 13,000 employees on its payroll [2016 figures].

BorsodChem intended to extend an existing plant to produce “aniline”, a key raw material for the production of another chemical called MDI. Aniline was not produced at the existing plant. The purpose of the plant extension was to replace the importation of aniline from China, simplify the production of MDI, reduce transport costs and avoid environmental risks linked to transportation of chemicals [and perhaps insulate the operations in Hungary from trade conflict]. BorsodChem would use itself all the aniline it would produce.

The eligible investment costs were HUF 45.4 billion (EUR 145.3 million) in nominal terms, or HUF 44.5 billion (EUR 142.2 million) in present value, composed of the cost of land, buildings, machinery & equipment, and intangible assets. All assets included in the eligible expenditure would be new and all intangible assets would be purchased on market terms from third parties unrelated to WIG and would be used exclusively in that plant.

The amount of aid, in the form of reduction in corporate tax, was HUF 14 billion (EUR 47.9 million) in nominal terms and HUF 13 billion (EUR 44.6 million) in present value, resulting in aid intensity of just over 31%. The tax reduction was to be utilised in five fiscal years after completion of the investment, depending on its actual profit.

Although not expressed as such in the decision, the Commission must have been concerned that existing assets could be used in the production of aniline. That eventuality created the risk that aid not strictly necessary could be authorised or that the project could artificially meet the thresholds laid down in the Regional Aid Guidelines [RAG]. For this reason it noted that “(18) as the investment concerns an initial investment in the form of a diversification of the output of an establishment into products previously not produced in the establishment, the Hungarian authorities provided information on whether the company has any existing assets – even if not included in the eligible costs – that would be used for the notified investment project. The Hungarian authorities confirmed that there are no assets that would have been in use earlier and would be reused for this project. Despite of the fact that the company owned the land already before this investment project, as it was not in economic use, the Hungarian authorities suggest applying zero as the value of the reused land. Therefore, the eligible costs exceed by at least 200% the book value of the assets that are reused as registered in the fiscal year preceding the start of works.” [paragraph 97 of the RAG requires that “for aid awarded for a diversification of an existing establishment, the eligible costs must exceed by at least 200 % the book value of the assets that are reused, as registered in the fiscal year preceding the start of works.”].

Single project?

Apart from the obligation for individual notification and prior approval by the Commission of this project, there was another complication. BorsodChem had received aid for three other projects at the same site in the previous three years. The aid for those three projects was also granted on the basis of the GBER. The corresponding individual awards had not been notified to the Commission because the sum of their amounts fell below the individual notification thresholds of the GBER.

However, with the envisaged award for the present project, the total sum of aid in the relevant three-year period had to be considered as a single investment project [SIP] and the whole amount had to be taken into account for the purpose of scaling down the aid intensity for large projects. Point 20(t) of the RAG stipulates that “single investment project means any initial investment started by the same beneficiary (at group level) in a period of three years from the date of start of works on another aided investment in the same NUTS 3 region”.

Point 20(m) states that “maximum aid intensities means the aid intensities in GGE for large undertakings as laid down in subsection 5.4 of these guidelines and reflected in the relevant regional aid map”.

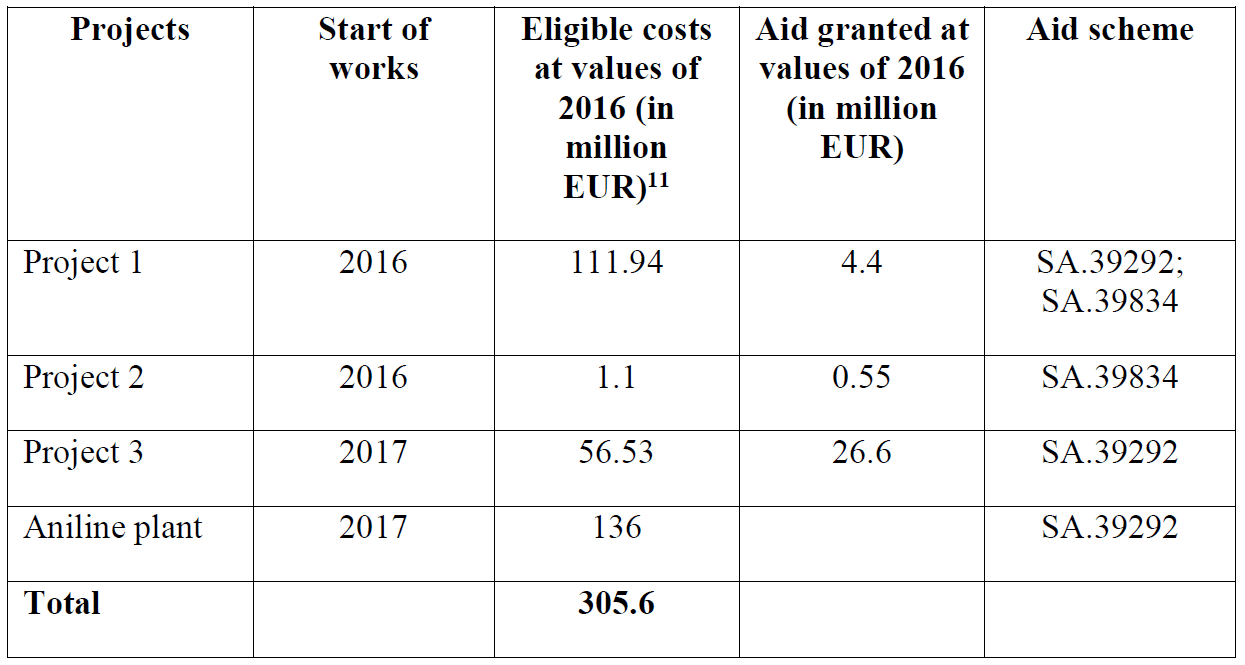

The table below [copied from the Commission decision] indicates the relevant sums.

As the Commission noted, “(27), the Hungarian authorities applied the scaling down-mechanism of paragraph 20(c) of the RAG; as the SIP includes all four projects, it could receive a total aid of 72.4 million. Since the first three projects have already received EUR 31.6 million aid, the project for which aid has been notified, i.e. the aniline plant project may not receive more than EUR 40.84 million aid at 2016 values. The notified aid (EUR 47.9 million in nominal value, EUR 44.6 million at 2017 values) corresponds to EUR 40.65 million at 2016 values, thus it remains below the maximum allowable aid amount calculated at 2016 values.” [The Commission decision does not explain at this point why it expressed everything in 2016 values instead of converting all figures to current values. However, later on in paragraph 130 it is stated that this is what the Commission did in past decisions. (The practice of using the date of the first rather than last project is also mentioned in the document on the Frequently Asked Questions.)]

Incentive effect

For regional projects which are individually assessed, it must be shown that the aid has an incentive effect. The incentive effect can be established by considering the counterfactual situation of either the profitability of the investment without the aid or the amount of investment costs without the aid in an alternative location. In this case, the counterfactual was the profitability of the investment without the aid, which was shown to be negative.

“(37) The Hungarian authorities provided relevant and genuine internal company documents in order to present the beneficiary’s internal decision-making process and to demonstrate that in the absence of the aid BorsodChem would not set up an aniline plant to supply its MDI production in [Hungary] but would continue to import aniline from WIG in China.” “(39) WIG has sufficient capacity in China to supply also the extended MDI production” in Hungary. “(44) The extension of an existing aniline Czech site would not have been an option as it would not serve the purpose of simplification and centralisation of the supply chain of MDI production” in Hungary.

“(46) In order to determine the profitability of the investment project (Net Present Value (NPV) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR)), the beneficiary’s finance team compared the costs of producing and importing aniline from China to Kazincbarcika to possible production and investment costs in Kazincbarcika. This was necessary, because the aniline market price for the profitability calculations could not be determined, as aniline is normally not sold on and bought from the market (minor quantities are traded on the spot market).”

In other words, the alternative to production in Hungary was not to buy aniline on the open market but to import it all the way from China.

“(48) The company considered the […] unit production cost as the “base cost” and calculated the additional costs and savings that would occur if the production were to take place in Kazincbarcika. To estimate the production costs at the Kazincbarcika establishment the production costs of the […] were applied as a benchmark”.

Production in Hungary would result in “(49) additional production costs compared to those in the WIG plants in China: The production cost […] in China would be lower than in Hungary, mostly due to lower direct energy and cheaper raw materials, (in particular cheaper […], which […] important raw material for the production of aniline).”

However, production in Hungary would also result in “(50) savings on the logistic costs of aniline if produced in Kazincbarcika compared to those if aniline is produced and imported from the WIG plants in China: BorsodChem calculated the savings on logistic costs inside and outside Europe (aniline is shipped to [EEA location] from China, and then transported from [EEA location] by train to Kazincbarcika) as well as the savings on customs duties that would be realised if the investment project is carried out in Kazincbarcika. These savings would exceed the higher Hungarian production costs (including direct and indirect costs) resulting into a positive operating free cash flow.”

“(51) However, this positive operating free cash flow over the reference period of 18 years (3 years construction and 15 years of operations, as the useful life of the core assets is 15 years) is insufficient to cover the investment costs of the company.”

“(52) Therefore, the financial analysis submitted to the BorsodChem Board concludes that the investment would lead to a negative NPV ([30-10] million EUR) and an IRR ([3-7]%) below the company’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC, [6-9] %) if the investment project is not aided. With a potential aid of EUR 47.9 million the investment could reach an IRR of [6-12]%, and an NPV of EUR [EUR 5-20] million. On this basis the Board approved the investment project on 19 December 2017.”

Do you know we also publish a journal on State aid?

The European State Aid Law Quarterly is available online and in print, and our subscribers benefit from a reduced price for our events.

Commission assessment

Since there was no doubt that the tax incentives constituted State aid, the Commission focused on the compatibility of the aid which was assessed on the basis of the RAG 2014-20.

First, the Commission considered whether the project could qualify as initial investment. “(72) Pursuant to paragraph 20(h) of RAG an initial investment means an investment in tangible and intangible assets related to (i) the setting-up of a new establishment, (ii) the extension of the capacity of an existing establishment, (iii) the diversification of the output of an establishment into products not previously produced in the establishment, or (iv) a fundamental change in the overall production process of an existing establishment. As the project (vertical integration) involves the diversification of the output of an establishment into products not previously produced in the establishment, it represents an initial investment within the meaning of paragraph 20(h) of RAG. According to paragraph 20(e) of the RAG, and within the limits defined in this paragraph, the costs for new assets for BorsodChem are in principle eligible for regional aid.”

Then the Commission explained that the common assessment principles are applied in three steps:

Step 1: The aid measure satisfies the minimum requirements concerning the credibility of the counterfactual scenario, appropriateness, incentive effect, and proportionality of the aid and contribution to regional development.

Step 2: The aid does not lead to manifest negative effects (blacklist) that would prohibit the granting of aid [e.g. aid exceeding the allowable maximum aid intensity ceiling, creating overcapacity in a sector in absolute decline, attracting an investment that would have gone without the aid to another region with a similar or worse off socio-economic situation, or causing the closure of activities elsewhere in the EEA].

Step 3: The contribution to regional development outweighs the negative effects on trade and competition [balancing].

Appropriateness

With respect to the appropriateness of State aid, the Commission noted that “(79) section 3.4 of the RAG therefore introduces a double appropriateness test. Under the first appropriateness test, Member States in particular have to identify the bottlenecks to regional development and the specific handicaps of firms operating in the target region, and to clarify to what extent bottlenecks to regional development could also successfully be targeted by non-aid measures. Under the second appropriateness test, the Member State has to indicate why – in view of the individual merits of the case – the chosen form of regional investment aid is the best instrument to influence the investment or location decision.”

“(80) The Hungarian authorities based the explanation appropriateness of the aid instrument on the economic situation of the situation in the Észak-Magyarország region and provided evidence to prove that the region is disadvantaged in comparison with the average of other regions in Hungary.” “(82) In this kind of economic situation, State aid has already been acknowledged by the Commission’s case practice as an appropriate means to address the economic shortcomings (e.g. in the Hamburger Rieger GmbH decision and in the MOL Petrolkémia decision under RAG, as well as in the Dell Poland decision and Porsche decision under comparable provisions of the Communication from the European Commission on the criteria for an in-depth assessment of regional aid to large investment projects).” “(83) Therefore, the Commission accepts that State aid, and regional investment aid in particular, is an appropriate form of support to achieve the cohesion objective for Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County, respectively Észak-Magyarország.”

Indeed, this is the Commission’s practice. However, neither past practice, nor the fact that a region is poorer than other regions explains why regional bottlenecks could not be removed by non-aid measures and why tax incentives were the best aid instrument. [Incidentally, I have argued elsewhere that multi-year tax incentives are more effective than up-front grants. See Grants versus Fiscal Aid: In Search of Economic Rationality, European State aid Law Quarterly, 2015, vol. 14., iss. 3].

Incentive effect

With respect to the incentive effect of the aid, the Commission accepted the approach of the beneficiary which was to determine the profitability of the investment project (NPV and IRR) by comparing the costs of aniline production in China and importation in Hungary, with the investment and production costs of aniline in Hungary.

“(98) As described in recitals (46) – (51) of this decision, the calculations demonstrated the following: aniline production cost in China would be lower than in Hungary, mostly due to lower direct energy costs ([…] production in China vs. […] production in Hungary) and cheaper raw materials (in particular […], which corresponds to about […]% of the raw material costs). In the case scenario where aniline is produced in Hungary, the savings on logistic costs inside and outside Europe as well as the savings on customs duty exceed the higher Hungarian production costs (even including the additional “operating costs of the new plant in Kazincbarcika”), but are insufficient to also offset the investment costs over the reference period of 18 years.”

“(99) The Commission considers the calculation of the 18 years’ reference period (3 years construction and 15 years of operations) presented by Hungary as acceptable, as it is not underestimating the expected free cash flow from the production in Kazincbarcika (as mentioned above the savings on the foregone transport costs and customs duties are higher than the additional production costs in Hungary, which means that the longer the reference period, the higher the possibility to cover the investment costs). The industry (including WIG and BorsodChem) determines a 10-15-year useful life for the majority of the core assets (machinery and equipment) that are connected with the investment in general. Longer periods cannot be determined, as the majority of the machines in question require significant refurbishment investments after 15 years. In addition, the Hungarian authorities provided benchmark examples from major players of the industry, which show that the average useful life of machinery and equipment vary between 6 and 15 years.”

“(100) The financial analysis submitted to the BorsodChem Board concludes that the investment would lead to a negative NPV ([30-10] million EUR) and an IRR (([3-7]%) below the WACC ([6-9]%) if the investment project is not aided.” “(101) The Hungarian authorities submitted information to the Commission on the way the beneficiary determines its WACC by detailing its cost of equity and debt. On the basis of this information the Commission considers that the WACC applied by the beneficiary is reasonable.” “(102) With a potential aid of EUR 47.9 million the investment could reach an IRR of ([6-10]%, and an NPV of EUR ([5-20] million. On this basis the Board approved the investment project on ([…] December 2017.”

Proportionality

With respect to the proportionality of the aid, when Member States grant aid to make investments sufficiently profitable, “(116) according to paragraph 104 of the RAG, the Member State must demonstrate the proportionality by using the method set out in paragraph 79 of the RAG and on the basis of documentation such as that referred to in paragraph 72 of the RAG.”

“(117) As a general rule, notified individual aid will be considered to be limited to the minimum, if the aid amount corresponds to the net extra costs (“net-extra cost” approach) of implementing the investment in the area concerned, compared to the counterfactual in the absence of aid. Pursuant to paragraph 79 of the RAG, in scenario 1 situations (investment decisions) the aid amount should not exceed the minimum necessary to render the project sufficiently profitable. The aid should for example not increase the beneficiary’s IRR beyond the normal rates of return applied by the beneficiary in other investment projects of a similar kind or should not increase the beneficiary’s IRR beyond the cost of capital of the company as a whole or beyond the rates of return commonly observed in the industry concerned.”

“(118) Based on the profitability calculation presented to the BorsodChem Board, the aid would render the investment profitable, as it would lead to a difference of [0.5-1.2] percentage points between the WACC and the IRR.”

Concerning the normal rates of return applied by WIG/BorsodChem, “(121) the Hungarian authorities presented eight similar investments of WIG and of BorsodChem carried out in the last 10 years. These examples demonstrated that the difference between WACC and IRR was significantly higher in the previous years’ investments. There was only one investment where a lower difference of [0.4-1.2] percentage points was accepted, as that investment was considered to be innovative.”

“(123) As the difference between the WACC and the IRR of this project is significantly lower than those applied for similar projects of the beneficiary and as the costs associated to lower utilisation in the Chinese plants of WIG is not factored in into the profitability calculations, the Commission considers that the aid is kept to the minimum necessary to render the project sufficiently profitable. Thus, the Commission considers that the proportionality of the aid is demonstrated.”

Manifest negative effects on competition and trade

Manifest negative effect: The (adjusted) aid intensity ceiling is exceeded

“(127) As the notified large investment project is also part of a SIP, there are two limits for the maximum allowable aid. First, it must be ensured that the aid does not exceed the scaled down intensity for the individual large investment project. Second, the aid for the entire SIP calculated on the basis of the total eligible costs of all projects may not exceed the maximum allowable aid taking into account the maximum aid intensity in the region and the scaling down mechanism.”

“(128) In application of the scaling down mechanism of paragraph 20(c), this leads to a maximum allowable aid intensity of 31.42 % GGE (Gross Grant Equivalent) for the individual project.” “(129) The envisaged aid of HUF 13 951 million (EUR 44.6 million) in present values (of 2017) for eligible expenditure of HUF 44 459 million (EUR 142 million) (both in present value) corresponds to an aid intensity of 31.38%. Therefore, the maximum aid intensity of the notified aid complies with the limit set for the individual large investment project.”

“(130) As a next step the maximum allowable aid under the SIP needs to be calculated. The four investment projects are considered a SIP in the meaning of point 20(t) of the RAG (see recitals (23) – (28) of this decision).” “(131) The Commission notes that the first three aid measures supporting the first three projects were not subject to individual notification obligation, as the aid amounts were below the notification threshold provided for in Article 6(2) of the GBER, even if they constituted a SIP. The earlier projects constituting the SIP started in 2016 and 2017. In order to determine the maximum aid intensity under the SIP, the values of the eligible costs and of the aid to all the projects (including the one for which the aid is under assessment) have to be time-consistent and comparable. Therefore, the eligible costs as well as the aid amounts have to be discounted to the date when the aid for the first project was granted, i.e. to 2016. The Commission accepted this approach in earlier decisions.” “(132) Applying the scaling down-mechanism of paragraph 20(c) of the RAG, the SIP including the four projects could receive a total aid amount of 72.4 million at 2016 values. The Commission notes that the first three projects have already received EUR 31.6 million aid at 2016 values. Therefore, the project for which aid has now been notified, i.e. the aniline plant may not receive more than EUR 40.84 million aid at 2016 values. The notified aid (EUR 47.9 million in nominal value, EUR 44.6 million at 2017 values) corresponds to EUR 40.65 million at 2016 values, thus it remains below the maximum allowable aid amount at 2016 values. Therefore, the notified aid complies with the limit set for the SIP taking into account the maximum aid intensity in the region and the scaling down mechanism.”

Manifest negative effect: The aid creates overcapacity in a market in absolute decline

After defining the product concerned, the relevant product market and the relevant geographic market, the Commission concluded that the project would not create overcapacity in a market in absolute decline.

Manifest negative effect: Counter-cohesion effect

Aid has a counter-cohesion when it induces the location of a project to a more prosperous region at the expense of investment in a less prosperous region. This was not applicable in this case.

Manifest negative effect: Closure of activities elsewhere/relocation

This was not applicable either in this case.

Overall, the Commission concluded the aid had no manifest negative effect on competition or trade.

Balancing of positive and negative effects of the aid

“(158) Paragraph 112 of the RAG lays down the following: ‘For the aid to be compatible, the negative effects of the measure in terms of distortion of competition and impact on trade between Member states must be limited and outweighed by the positive effects in terms of contribution to the objective of common interest. Certain situations can be identified where the negative effects manifestly outweigh any positive effects, meaning that aid cannot be found compatible with the internal market.’”

“(159) The assessment of the minimum requirements demonstrated that the aid measure is appropriate, the counterfactual scenario presented is credible and realistic, the aid has incentive effect and is limited to the amount necessary to incentivise the beneficiary to adopt a positive investment decision. By triggering an investment in the assisted region, the aid contributes to the regional development of the Észak-Magyarország (Kazincbarcika) region. In addition, the aid will have a positive effect on the environment, as it contributes to the reduction of environmental risks stemming from long distance transportation of toxic materials. The assessment also showed that the aid has no manifest negative effect: it does neither lead to the creation or maintenance of overcapacity in a market in absolute decline, nor does it lead to excessive effects on trade; in particular, it respects the applicable regional aid ceiling, has no anti-cohesion effect, and has no causal link to the closure of activities elsewhere and their relocation to Kazincbarcika. In addition, the aid does not entail a non-severable violation of EU law.”

“(160) Moreover, the Commission has to include in its balancing assessment undue negative effects on competition as identified in paragraphs 114, 115 and 132 of the RAG; i.e. the creation or reinforcement of a dominant market position or the creation or reinforcement of overcapacities in an underperforming market (even if this market is not in absolute decline).”

“(161) The Commission considers that the aid does not lead to (or reinforces) a dominant market position of the aid beneficiary, given that the aniline produced as a result of the investment is not sold on the market and the investment does not lead to further capacity creation in the MDI market. Consequently, the aid does not lead to the creation of overcapacity in a market in decline. The aid is limited to the amount necessary, and thus does not make available “free money” to the aid beneficiary. It has therefore no negative effect on competition.”

“(162) The effect of the aid on trade between Member States is limited as mainly the aniline produced and imported from intra-group will be replaced by own production in Kazincbarcika (the aniline quantity purchased earlier from third parties located in the EEA was marginal and the company does not plan to continue buying from these suppliers in any of the alternative scenarios). Aniline is an intermediate product and will not be sold on the market but will be used to supply the MDI production of the establishment. The total MDI output will be the same regardless of the investment project. Thus, the effect of the investment on trade flows between Member States would be very largely the same whether it takes place or whether the beneficiary continues to import the aniline from the intra-group companies located in China.”

Conclusion

This is a textbook case which despite its complexity was well-documented and argued by Hungary. It shows both the strengths and weaknesses of the methodology on which the current RAG are based. The necessity, proportionality and possible anti-cohesion effects of regional aid are thoroughly and rigorously assessed. The examination of the appropriateness of aid comes across as a formalistic exercise with the Commission falling back on past practice, even though the case law says that each case has to be assessed on its own merits. Despite the claims to the contrary, the balancing of the positive and negative impact of the aid is in reality a test for checking the absence of undesirable effects. At least the RAG do label these effects as “manifestly negative”. It would be good if in the forthcoming revision of State aid rules the Commission drops the word “balancing” and adopts an explicit list of manifestly negative effects. Or, if it is afraid that there may be something unforeseen that will escape inclusion in the list, it can give itself the option to exercise its discretion in those rare cases where necessary and proportional aid proves to be too distortionary.

————————————————

[1] The full text of the Commission decision can be accessed at:

http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases1/201931/272537_2086178_134_2.pdf.